The Voice Director Presents: Let’s Talk Voiceover

Episodes

Saturday Apr 08, 2023

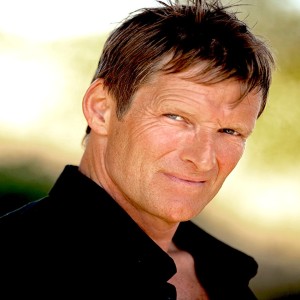

Let’s Talk Voiceover_Episode 40_Jeff Howell

Saturday Apr 08, 2023

Saturday Apr 08, 2023

Although trained as an actor, Jeff has had a varied and storied career in voice acting on the other side of the glass. Voice Director in comedy radio, promo & animation, a former Agent, and Production Executive; he is now an in-demand Dubbing Director, with shows on every major streaming network. He is also one of the nicest human beings in the business as well as being a highly respected voice acting coach. There's a lot to digest here, so settle in!

Sunday Jul 03, 2022

Let’s Talk Voiceover - Episode 37 - Mark Estdale

Sunday Jul 03, 2022

Sunday Jul 03, 2022

Mark is one of the most well-known and credited video game directors in the world, casting and directing actors in titles such as Warhammer, Tropico, Wallace & Gromit, Need for Speed, and so many more. He's been at the forefront of the creation of the industry. and he's still a bit of a mad scientist: creating, tweaking, and pushing the technology envelope. He has his own definite style and a deep love of the craft of acting. We got to have a rare in-person interview with him, where he put us in separate booths so we could experience "the lab" that is his London studio OMUK. This is what came out!

Randall Ryan:

You want to do a sync clap? Just like one, two, three? It'll just make it easier for me to sync the three feeds.

Gillian Brashear:

All at the same time?

Mark Estdale:

Yeah. You're recording now. Do it now.

Randall Ryan:

Let's do it now.

Gillian Brashear:

Okay.

Mark Estdale:

Okay.

Randall Ryan:

All right, here we go. Three, two, one. Way to go, Mark. You didn't clap.

Mark Estdale:

Oh, you want me to clap as well?

Randall Ryan:

Yeah, all three of us.

Mark Estdale:

Okay.

Randall Ryan:

Three, two, one. Perfect. Close enough.

Mark Estdale:

Ish.

Gillian Brashear:

Nice.

Randall Ryan:

It's ish, it's ish, yeah.

Gillian Brashear:

Right. We're ready to roll here.

THEME MUSIC

Randall Ryan:

Mark Estdale is one of the more fascinating personalities in our industry. Over 25 years, he's directed more than 140 video game titles, including some very well-known franchises, Warhammer, Tropico, Need for Speed, Wallace & Gromit, The Witcher, and Tales of Monkey Island. He's an innovator who really pushes the technology envelope when it comes to casting and recording. Gillian and I had a rare in-person conversation with him at his London studio, OMUK, which he refers to as the Petri dish.

Gillian Brashear:

Mark Estdale, let's talk voiceover.

Mark Estdale:

Let's do that.

Gillian Brashear:

Yeah.

Mark Estdale:

And you're in the lab.

Randall Ryan:

We are in the lab.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah.

Gillian Brashear:

It's a bit of a mad lab.

Mark Estdale:

It is a mad lab.

Randall Ryan:

Mark, when did we first meet? Do you even remember?

Mark Estdale:

Fuck knows. I have no idea. It's a few years ago anyhow, so.

Randall Ryan:

Interesting conversation that you and I were having just a minute ago about how you got into this because ... Mark, hey, look at the guitars. Are you a musician?

Mark Estdale:

No. I play for myself. It's a meditation. I ended up messing around with music, which, fundamentally, has to do with being with people and doing interesting creative stuff. I think musicians have, people have a degree of competence and can produce music. I doodle and from doodling sounds happen. Connecting those sounds is another art form. I doodled all my life. And I went to run a studio for a record company and I brought my doodle tapes. I would get my mates into the studio. We would just experiment with stuff. It was the beginning of digital. The only music I was working with was experimental industrial stuff in the '70s and early '80s. And you were going out recording foundries and factories and noises. And then making tape loops and running tape loops in the studio and experimenting with all that kind of stuff.

Mark Estdale:

So the art of replacing sounds with other sounds was about cutting tape and doing all that kind of stuff. So, my deal was the studio. They paid me fuck all. When I wasn't in session, I had free rein of the studio to do what I wanted. So I just record staff and have friends around and some of the musicians, we'd just experiment with things. So I basically transitioned to another studio with my tapes. The owner of the record company went, I want to give you a deal. And I went, great. And then, suddenly, it became work. And all the pleasure went out of it. And I went blind in the sense of there's no way I can mix my own stuff. I can't direct myself as an actor. So I'm on a journey as an actor right now. So I'm doing training right now.

Mark Estdale:

But yeah, we did a single and it was great. Let's have the album. And it was just like nah, nah. It's too much light work and it doesn't come from the heart and out of the weirdness of it, but I'm still planning. So I've been building instruments and I bought interesting drums and things and just things that just got weird sounds. But the world has changed dramatically since my skill as an editor was with a razor blade.

Randall Ryan:

Razor blade, right.

Mark Estdale:

And then when digital came in, I got really into that early ... We were mastering to Betamax and things like that back in the-

Gillian Brashear:

Right.

Randall Ryan:

Yeah.

Mark Estdale:

That was in the, I think that was the early '80s when that all came in. Then, my journey took me away from that. But I got into the whole music stuff that it was just farting about, trying to break things, trying to do things that were interesting. You wouldn't call it music per se.

Randall Ryan:

But the thing is that you produced. You produced albums, you produced singles, you produced bands.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah.

Randall Ryan:

Well, I mean you did. And so-

Mark Estdale:

Yeah.

Randall Ryan:

I've talked about this before. Actually, one time, you and I were at Buca di Beppo in-

Mark Estdale:

What? What is that? Where is that?

Randall Ryan:

Well, it's this little place where they can ... Yeah.

Mark Estdale:

Somewhere in LA.

Randall Ryan:

D.B. Cooper had organized something.

Mark Estdale:

Oh yeah, that'll be in, yeah, that'd be in San Francisco.

Randall Ryan:

Yeah, so it was in San Francisco, right. You and I were talking about this at Buca di Beppo, which is the first time I knew you had anything to do with music. And you were talking about the band that you did and just how you were taking all these electronic pieces and parts and stuff and putting them together. And I just remember listening to that going, this guy's a producer. And that's probably, I'm guessing, somehow how you got to doing what you're doing now.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah. Well, the thing is I came from performance originally. So, one of the things I got into was acting, but it wasn't really starting as acting. I was just a bored teenager on the street with a mate. We'd used to sit and watch people, then mimic people. The game we played was copy somebody and see how close you could get to them and copying all their mannerisms, just walking down the street. And it was just hilarious. We got more and more outrageous, making it bigger and bigger. And we would gather an audience. People would see us doing it than just stop and watch. And the person we were mimicking was completely unaware of it.

Randall Ryan:

That was going to be my question. Like, people started to come up going, do me?

Mark Estdale:

No, no, no, no. It was just us and about. But we had so much fun doing it and it was a real buzz from it. I was 15 at the time. And then, yeah, we started doing a bit of sketch stuff and I just loved it and I thought I really wanted to be an actor, but I'm deeply dyslexic. I got thrown out of school at seven. And it's a long brutal history that goes behind that. And one thing about acting was learning words and scripts. And I just, I can't do that.

Gillian Brashear:

Are you able to learn and memorize without reading it? Like just listening and memorizing?

Mark Estdale:

Nah.

Gillian Brashear:

No. Interesting.

Mark Estdale:

Nah, I can't even memorize what's in my own head. I'm an endless note-taker now. So I think on paper and on screens. But I love words. Being dyslexic gives me a, I think, a massive advantage in doing what I'm doing. Because in the studio I've learned that playing dumb is the blessed place to be. It's proven to be in a sense. I also get ill where I can't talk.

Gillian Brashear:

Really?

Mark Estdale:

Yeah. I can't remember the name of the disease. But essentially, if I talk I get stomach acid in my lungs, which would destroy my lungs.

Gillian Brashear:

And so then physically, the ability to talk, it's shut down or you just-

Mark Estdale:

Yeah. So it becomes ... I get into a state of uncontrolled coughing because, basically, your stomach acid is eating in your lungs.

Gillian Brashear:

My gosh.

Mark Estdale:

So it's potentially a very, very dangerous disease, but it's just a tiny thing. So, if it starts, I start coughing, that agitates it, and it gets into a loop. So, fundamentally, I can't talk. So, when I first got ill, I was in the studio and I had to communicate completely nonverbally. So that was a really interesting learning space too, because it was all about body language and communication. And the studio was set up like a regular studio where the engineer is in the main position and the director is at the back or somewhere else. I prefer to be in the booth with the actor if I could, but I'm far too noisy. So the glass is a necessity. But then I realized having this level of intimacy where it's between you and I, and it's about that trusting relationship. And one of the things about not being able to speak is then to be able to communicate ... I became Silent Bob. All hand gestures, things gestures, but it became a really intimate way of directing. And just the performances that were coming out were just great.

Mark Estdale:

And I just thought, okay, director, shut up. And in the studio, it's that whole sense of you want the performer to perform. We speak 9,000 words an hour. And sometimes, especially when you're doing the advertising stuff, you'll have a team of people just chatting away in the control room. The actor's doing nothing. Or then the director is talking, talking, talking. You're actually paying the actor the most to do the performing. And the ratio between performance and chatter, there's a tendency to be more talk here than in there. And just from the fact of being ill, observing that process and going, okay, this is liberating the actor in certain ways. That was interesting.

Gillian Brashear:

That is interesting.

Mark Estdale:

I've learned to just ask those straight questions. So rather than directing somebody, being in control, doing all that background work, it's been in the moment and going, I don't understand this. So we work in the studio exactly like we are here now. We're all talking to each other. And what I do is have the writer in. I'll have currently those people on Zoom, which is horrible. But generally, there's a group of people here and the whole idea, this is a collaborative process. So there is no talkback button. It is always open. So you are coming into the studio space to do your part, but we're working as a team. And it's exploring together.

Mark Estdale:

So, my default for directing is not talking to the actor, it's talking with the writer or questioning the script in an esoterical way or just going, I don't really understand this. What do you think? I go, what do you think, and joining into a conversation and letting the actor take from what is being said what they think is necessary. It's a non-pressure thing. But actually playing the dumb guy in the space, to ask the stupid questions is the liberator.

Gillian Brashear:

It allows the space for things to happen.

Mark Estdale:

And I think that was the thing when you mentioned earlier about record production and all that kind of stuff. It never came to where I wish I was doing it now because I know so much more. But the one thing I really noticed was having the studio as a liberating space was the most important factor of getting a great performance. Like bands in rehearsal rooms, in their own space, can produce magic and be fluid. Come into a studio, that's that level of stress. Then you'll say, recording, that's another level of stress. So, I looked at everything down the line, which actually liberated that space, that stress. So for instance, the space here is a living room.

Randall Ryan:

Basically, yeah.

Mark Estdale:

It's a den. It's somewhere to come and feel at home and you want to relax in, you want to hang out in it to feel safe. It's breaking down those barriers. So for instance, the recording engineer is working like recorders on film set. They're out of sight. It's all about the action. It's all about living in the fluid space, without words into the moment of the game. They're absolutely in the game. It's about immersing them in the game.

Gillian Brashear:

What do you mean by that? That you're immersing them in the moment of the game. How do you do that?

Mark Estdale:

The one thing that you need to be connected to is the game. I always think artwork is a corpse, animation is a zombie. An actor embodying the zombie, bringing it to life, is a fully realized character. So, all of those elements are really powerful. So with the game developers, say, they've been working on a game for five years. If you've not cast early, you are dealing with a team of people who have got a voice in their head. And every single person will have a different voice in their head.

Randall Ryan:

Yep, absolutely.

Gillian Brashear:

Mm-hmm.

Mark Estdale:

So you're competing against that.

Randall Ryan:

Absolutely.

Mark Estdale:

Well, the phrase that's used always is, fuck yeah. Casting is about fuck yeah.

Randall Ryan:

Yeah.

Mark Estdale:

It's just like, yes, that character is fully alive within the orchestra of the ensemble. And if you cast early and the developer's going, fuck yeah, there is no doubt whatsoever about the character. There is clarity at that point. And then you can move that character in different directions. You may even want to recast it because it doesn't quite work within the context of the world. But what you have is a united vision, early, and that is so powerful because it influences the nuance of the writing. It influences the nuance of the animation. Every element is feeding each other. And by the time you come to record, you are already well ahead. And we want the actor engaged in that process, within those discussions that we have with the developer, so they're part of that process of developing a character.

Randall Ryan:

So, because the culture is so strong for casting late, doing all the VO late in the development of the game ...

Mark Estdale:

Yeah.

Randall Ryan:

... how do you get people to buy on to, hey, we need to do this now. Scripts aren't even written a lot of times.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah, they don't. We don't need them to be written.

Randall Ryan:

You still buck up against the culture.

Mark Estdale:

We are the culture. Those ideas are the seeds. You are bringing in a master of character in an actor, somebody who knows how to interpret and to bring that character to life. You're bringing that level of craft and expertise into the team to weave magic within that team. You need to just talk about it like this and people go, oh yeah.

Randall Ryan:

Right.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah. But that's the way we roll. The sausage factory of just churning it out at the end..hey, that is an opportunity to do magic beyond. So if we're working on a big plan, they're just throwing everything to the universe, and I'm working with an indie with no money. We can so outperform, outclass with so little.

Randall Ryan:

Absolutely.

Mark Estdale:

Simply because of the depth of engagement. And that depth of engagement costs bugger all. But it's a human engagement in a process and it's a creative journey you're embarking together. It makes a profound difference.

Gillian Brashear:

Absolutely. And it makes use of what actors do and have early in a process. It makes so much sense now listening to you ...

Mark Estdale:

Yeah.

Gillian Brashear:

... that for the writers to be able to hear the words while they're still in the process of making it all, but actually hearing a character must inform the writing aspect in such a more rich way.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah. We look at games that we've worked on that are ongoing franchises, which is a really good example is a game called Vermintide, which is a Warhammer game. And there are a bunch of player characters. And it's all about the interactions between those player characters. As soon as the actors came on board, the characters became fully alive. And over the years, each time we record, the actors bring feeds, the writing feeds, everything else, and feeds the humor and the humanity of everything. The way the dialogue works is really interesting as well, because it's not just straight dialogue, you're using buckets. So, conversations are actually built up.

Randall Ryan:

So you're randomizing some of the responses?

Mark Estdale:

Yeah. But the way that the whole system here works is the actors are always working with each other in the booth, in that random space. We're not ensembling it because ensemble won't work in the situation. But they're always working off each other and adjusting, and everything becomes this fluid movement. So, the cast is now mature. The game is now six years on. But the writing has become funnier and funnier and more nuanced.

Randall Ryan:

So are you doing playback? Here's just some random playback for you to respond to.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah. There's a thing called CDT. There's creative dialogue tools. And fundamentally, what creative dialogue tools does is connect any game asset to the script. So for instance, you've got this script in front of you. You can see here. So, you've got this bit of dialogue. And whatever's going on, it can be video, so you've got character scene, item video. So, anything visual is there. I don't need to explain that conversation to you. You know where you are. We also got the voices of the actors. Source that if it's another language. Spot effects, those are just things that may interrupt, like an explosion or a door slamming or a sonic interruption. Then you have ambience, which is the ambient noise of the thing. And then music. So all those layers are available instantly. So what the CDT does is connect all the potential game assets to the script, so the actors in the movement. So this one is just this scene here is you're in a bar. This is Randall. He's talking to Elaine.

Gillian Brashear:

Randall, you're talking to Elaine.

Randall Ryan:

Well. She was there. She bought me a drink. What are you going to do?

Mark Estdale:

So, you can just go in and act this straight away, but I've got the Randall line straight here. So you can go off, you're off.

Gillian Brashear:

I'm nervous since you're here. More like barracudas. Okay, good. ´Cause I don't.

Mark Estdale:

So she's straight into ... She knows the scene, you know the level, you know everything, you are utterly connected.

Gillian Brashear:

Yeah, this is fun.

Mark Estdale:

Exactly. And that is the response. You're entering the roller coaster.

Gillian Brashear:

Yeah.

Mark Estdale:

So the actors are coming in just going, they just make choices and run.

Gillian Brashear:

Yeah.

Randall Ryan:

Yeah.

Mark Estdale:

I was talking earlier to you about the neuroscience of this. This is where I'm super excited, but I can't really articulate much of it now. When I first started doing game stuff, one of the things I really noticed was you'd be really diligent and give actors the script in advance and they will study it-

Randall Ryan:

When you can.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah, when you can.

Randall Ryan:

Right.

Mark Estdale:

The actor will prepare and come in and do their thing with the context of the directors who knew the background work and got the choices and all that kind of stuff. But then if you gave the actor a side they'd never seen before and say, just go, oftentimes their very first read, it'd be just knock the ball out the park. And I was going, what is going on here? So I never ever give actors a script in advance. Never. It doesn't matter how intricate it is. There was this really profoundly personal dark journey a character had gone on. There's this monologue, long monologue. And I thought, this is one to give in advance, but I didn't. I decided not to. And he hit it in one take. And by the end of it, we were all in tears. And the actor didn't know what was coming. They didn't know what the next sentence was. They didn't know what they were going to expose about themselves. It was profound for us in the studio here. We just go, fuck yeah.

Gillian Brashear:

Mm-hmm. I think it's got something to do, when I listen to what you're saying, the element of discovery.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah.

Gillian Brashear:

And when the actor is allowed to discover in the moment, the reactions they're going to have are very fresh and real. They're not manipulated.

Mark Estdale:

When I first started experiencing this ability to just live in the moment, I was thinking about where in the real world does this kind of acting exist? In theater, it's within improv.

Randall Ryan:

It's improv, right, exactly.

Mark Estdale:

But an improv is part of devising, part of knowing…

Gillian Brashear:

Mm-hmm. Rules.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah. However, in the real world where that improvised space is happening is when somebody's working undercover. So if you've got a cop who's working undercover, they are acting, they're being somebody they're not. And they have to survive in the world and their life is at stake. So that is improv extreme. Somebody from MI6 came down to the studio and couldn't talk about anything. But then he said, I would take it, I would take ...

Gillian Brashear:

It was a silent session.

Mark Estdale:

But what he said to me, he said, this is what we do, but for fun. And he's like, I can't tell you anything, but I can take you on a journey. And an interesting journey unfolded after that. That thing about living in the moment, I was really curious about how can you cold-read a script? Because somebody working undercover is total improvisation.

Randall Ryan:

Absolutely.

Mark Estdale:

Improvised theater is improvisation. But having a script and reading it, how come that works cold? And I was really curious about that. Basically, our brain is so much faster than we think it is. The thinking, speaking part is a linear element that comes from insane complexity. But if you think of the connections in the brain that are happening and firing at all times, if those connections were a ball of Christmas tree lights, that ball of Christmas tree lights would be the size of the known universe. That is the complexity and the power and the speed of our brain. We're coordinating everything at any one time. So you're trusting our humanity. The choices we make are always instant. If you go out on a date, and you prepare things, you just fall over yourself.

Randall Ryan:

Yeah.

Gillian Brashear:

Mm-hmm.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah. But if you don't care and you relax and you yourself, you come out and it's enabling that to happen. There's a lot more depth to the neuroscience of it. One of the really exciting things that's happening in cognitive science is the merging of psychology, of neurology, of physiology in their language and understanding. The connection between that and what's happening in the scientific world about how the brain works is so exciting. And the thing is, actors have known the essence of that and have created their own language about how we function because they're questioning how we function.

Mark Estdale:

Anybody who studied acting or taught acting is looking about how do you become another character, how do we embody fully somebody we're not? And that's the essence of the heart of the craft of acting, but it's studying humanity from a creative point of view. Whereas the science, the cognitive world is thinking about exactly the same subject from a scientific point of view. And those two worlds are converging.

Mark Estdale:

Rizzolatti, the Italian neurophysicist discovered mirror neurons. And mirror neurons are those neurons that respond ... I think some 300 people or 3,000 people probably take me in a corner and beat me up for getting it wrong. But they are the things that ... They're our imagination. So if I tell you a story, you will have an emotional response as if that was real.

Randall Ryan:

Right.

Mark Estdale:

I remember when I was at the Game On thing in LA and I talked about my fingers being broken.

Randall Ryan:

Oh yeah. Right.

Mark Estdale:

And the whole audience went ACCK!, you know what I mean? We learn from other people's experience.

Gillian Brashear:

Absolutely.

Mark Estdale:

And that is why theater is so wonderful.

Gillian Brashear:

That's storytelling in itself.

Mark Estdale:

It's storytelling.

Gillian Brashear:

Yes.

Mark Estdale:

The whole art of storytelling.

Gillian Brashear:

Right. That's why we do it. It's our shared consciousness.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah.

Gillian Brashear:

We're learning from your experience.

Mark Estdale:

Now science is beginning to go, oh, there's all these connections. So you've got embodied cognition. You've got a thing called 4E cognition. We're not just a brain in a head. We're a brain in a body. It's that physical connection. So, you get embodied acting. Then you get transformative acting, which is taking a step further. If you look into the relational stuff that Uta Hagen talks about what is the relationship between you and an object or your environment, really important. But this 4E cognition is about the cognitive process is connected fully to the environment, not just to head, not just to body, but it is external as well as internal. So, it's to do with spaces and containers, and containers is the thing I'm really interested in. That's when the new studio lab is going to be built, is looking at that research into containers.

Mark Estdale:

I can talk about this for hours and just go, because it is really interesting. But the fundamental thing is it's about how to liberate somebody in that moment. For an actor coming into the space, it's about being. One of the things I advise in auditions. You can hear when somebody's crafted it and reread something first. You can hear somebody living in the moment. You can hear when somebody's directed. You can hear when an actor is stuck in front of a microphone. It's a cage. I am caged. Because I keep moving off mic and you can hear it. That means it's a bad take. You will never give me a bad take. So when we're casting, what I recommend now is don't look at the sides, look at the character. Yeah, think about the context of who you are, what you are. Look at the context for the lines, not the lines themselves. Then cold read the lines, then press send. Without reviewing it, listening back or anything. If you fluff it, stop, start again. But keep that in and just give one take, send it.

Gillian Brashear:

I like it. I like that whole idea.

Mark Estdale:

Because it's about coming ... You're making a choice. So when I'm casting and having people in the studio, when somebody have made a decision, you have something tangible that you can flow with. And they've come in with a decision, you are throwing them into something and they're going with it. And then you can go, how about this? And they go, oh, different decision, let's go that direction. That's what I'm looking for in casting. That's all. Actors are coming to the booth wanting to please me.

Randall Ryan:

Right.

Gillian Brashear:

Right.

Mark Estdale:

And it's just dead.

Gillian Brashear:

Yes.

Mark Estdale:

It's never going to happen. And it's what I call licking. People want to lick you. It's like uh-uh, make a choice, run with it and let's play. They're entering a playground. They're being a child. And that is what training really gives people, that ability to play and to be safe and have confidence. We get actors bouncing into auditions and it's just like, okay, let's play. It's always a learning experience. And they're less invested in trying to please. And the more they're embedded in being the better chance they have. And the tough thing is, the actors who are really experienced know that. But that's why we have these agent sessions, where the agent comes and sits in here and we'll discuss everything and do the same thing as if I'm directing a session, open mic, just mess around. Here's a scene. I go through these scenes here with the actor, throw them about and introduce them to it. And this is basically what I call a no-risk session. So, we have a very strict score system. Four is on the knows. Zero is what the fuck. So, fuck yeah to what the fuck. Yeah.

Randall Ryan:

So one is I don't give a fuck. Two is ...

Mark Estdale:

You could give a fuck.

Randall Ryan:

Could give a fuck. Three is fucking pretty good.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah.

Gillian Brashear:

The four levels.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah, we could have the fuck scale. Yeah, we haven't thought of that. But I think, we actually do do that, having the fuck scale. The Randall Ryan fuck scale, that's what we're going to call it.

Gillian Brashear:

Four levels of fuckery.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah, exactly. So, we'll zone people.

Randall Ryan:

Right.

Mark Estdale:

To start with. So it won't go into refined. This will be a three, four or a two, three or a one, two, or a zero, one on their first take. That to me is meaningless. Because what happens, you are dropping somebody into the playground for the first time and they're going, do I like this, do I want this, do I embrace this? Then they go away and they think about it. And if they want to come back, they'll be a different person.

Randall Ryan:

So when you're casting with this, when you're doing things like that, is that either you're already thinking about casting them and so these are like call back auditions, because you probably can't do that with everybody, right, unless you have a really small number of people that you're calling from.

Mark Estdale:

We get people to self-take. The casting side's really important.

Randall Ryan:

Right. Of course.

Mark Estdale:

Because that score system exists. We have a thing called the casting matrix. I think I can bring up a matrix for you, which is terrifying because it's another sheet. Yeah, Google Sheets is wonderful as well.

Randall Ryan:

Do you realize this visual stuff is great for a podcast?

Mark Estdale:

Yeah, that's perfect for a podcast. But it's fundamentally. So this is a casting sheet. This is sanitized so you don't see all the actors on it. Fundamentally, get their scores. Our casting briefs are really precise. And within it, there is a description of how to submit, what to submit. So we'll say things like don't slate your sample. So if an actor slates the sample, they don't get listened so they go straight to the bin.

Randall Ryan:

I've told so many people that exact thing. Thank you for saying that.

Mark Estdale:

Well, the thing is if somebody can't follow instructions when they want a job, how the fuck are they going to listen when they're on their job?

Randall Ryan:

100% agree.

Gillian Brashear:

Mm-hmm.

Mark Estdale:

So there are details within the casting submission, which adhere to or be damned. And the other thing is, so the way we look at the casting is each actor, if they're going to submit for multiple roles, their best score is going to be the average. So if they submit for one role and nail it, they've got top score.

Randall Ryan:

Yeah.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah. We've got some down here that submitted for a couple of roles. They've nailed one, but they submitted for three, and they're off the scale down here. They were four for one role, but they wouldn't be considered for that role or they wouldn't be the top choices for that role because their average was lower. And the reason we do this is, one, it's about self-awareness. It's also about production awareness. So when you submit, it takes at least 20 minutes to listen through to a sample. And oftentimes, when we're in casting, three people will listen to that sample and make notes. That takes time. Yeah. If you're carpet-bombing want to be hopeful and you'll say, oh, I'll go for this one and go, you are wasting our time. You may be brilliant and be able to nail them all, but get through your door on one is all you need to do because we can play once you're in production.

Randall Ryan:

Okay. So let me give you a little devil's advocate on that.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah.

Randall Ryan:

So, unless you are doing one-to-one casting, one actor, one part, one part, one actor, even if you're submitting for roles that maybe you don't get, if you're submitting for something that you have no business submitting for, that's a faux pas. But you submit for that one role that, as you said, you nail. And then maybe you submit for a couple others, like they're okay, they're average, they would work if we had to work with them. Isn't there something positive to that if you are having to say, they're going to get that main role of rows, this actor is just perfect for rows? I can give them two other roles. I can give them an NPC. I can give them maid number eight.

Mark Estdale:

That's my decision, not yours. It's a production decision. So this is about getting through the door. You do a self-submission, submit your best. Because then, if we don't know you, we'll call you in and then we'll mess with you. We'll send you on a roller coaster. So we'll play around with that character because we want to see about adjustment. The self-tape tells you nothing. Some self-tapes, whether that actor can really do it, especially if it's somebody you don't know, it may have taken hours of crafting and all that kind of stuff. So, it's saying, yeah, this works, but I want to see it work under production conditions. If we don't know the actor, then we'll bring them into the studio, put them into production conditions. And during that exploration, we will explore other characters.

Randall Ryan:

Well, this is something you can do because of what you said, where you are getting casting done early. That gives you that luxury of that.

Mark Estdale:

But it's always pushing that casting time. Having casting time is ... Casting is king, is everything.

Randall Ryan:

Yeah, it is.

Mark Estdale:

We cast wide all the time. So, probably the casting backlog is about thousand actors right now within productions. We've got all these samples. So, Zach here and Nat are going through those building the database. So which is the matrix here, which is scored. So every sample gets a score. And the average score is the actor's in through the door score. So if they come in, they cast, they go, that is the role I want. If the actor is undecided because they're so brilliant, just come to make one choice. That is the message. Make a choice. Because if it's good, we will call you back for other stuff anyhow, even if you don't get the role.

Mark Estdale:

So this is statistics. And this also gives us statistics about the agent and every statistic tells a story. So, the average score from the actors then becomes the average scores to the agents. So we basically expect agents to do a lot of the work for us. So we will send the briefs to the agent. And if the agent is really hot, they know their talent, and they go, he'll be good for this role. Or she'll be great for this one. And they will send specific actors.

Randall Ryan:

And they don't give you 10 to show that they've got a bunch, which happens a lot.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah. So some of our agents will just send us three samples.

Randall Ryan:

Right.

Mark Estdale:

And they all go bang, bang, bang. They're in the bag. Oh, nice agent, good, saved us time. And others will get all the briefs come in. They just put it onto their website for any actor to put in whatever they want. And they just pipe it all to us and we'll get 100 submissions.

Randall Ryan:

Absolutely.

Mark Estdale:

Do we want to work with that agent? Do you know the production cost of dealing with that and waiting through that? And some of those samples will be shocking. So having the agents in here for these agent sessions, we talk about this thing. And so we are evaluating the agent as well as the actor. And if we get carpet-bombed, okay, they don't understand production and they're not putting their best foot forward. They're just being hopeful or hoping something will stick in there. And that ain't good practice. We don't want to work with those agents who carpet-bomb because it is wasting our time. It's making them look really crap. The data tells a story. So we know when an agent's carpet-bombing and there's no filtering.

Randall Ryan:

Do you try to train the agent at all?

Mark Estdale:

Yeah. That's why we invite the agents down. So we've got two sessions this week with different agents. They're coming down from different agencies. So oftentimes, agents don't get to really know their crew, the actors. There's hundreds of actors on the book. And it's a real opportunity for the agent to get to know the talent, which they wouldn't normally get within the normal working day. And it's about us educating the agent, educating the actors. And that is the fundamental thing. And we find gems in doing that. So we have a massive database. Every single casting that comes through here goes onto a database. We have all the score and their average score over everything, and the notes. Every sample that comes in is an asset for the database. So there's tens of thousands of the data thing.

Gillian Brashear:

My gosh, it's incredible that you have time.

Mark Estdale:

But it means it's all at the fingertips.

Gillian Brashear:

Yeah.

Mark Estdale:

So for on a production side, you want that sense of know who you are as an actor. Put your best foot forward, what you think you're great for.

Randall Ryan:

Okay. So let me ask you something else then.

Mark Estdale:

Go on.

Randall Ryan:

So, let's just say you're precasting for a game. You've got a main role for something. And an actor submits for that. And they give you two different submissions for it that are radically different from one another. But they're making choices like here's one way I could play it, here's something else I could see. Or maybe the first one is, here's something that is absolutely in spec based on the brief. I have an idea on something else and I just want you to hear it. I mean, that's their thinking. They may not say that in the audition because they're just going to give you a couple of things. In your world, is that a positive, is that a detriment, could it be either?

Mark Estdale:

In my world, I would say it's a detriment.

Randall Ryan:

Reason being?

Mark Estdale:

Make a choice.

Randall Ryan:

What if they have, they've made two choices?

Mark Estdale:

They made two choices. Choose between one of them. Run with it. Yeah. What's your gut feel? Sometimes, they may want to go off the brief, fine. It is about conviction. Conviction carries.

Randall Ryan:

Okay. So if what they're doing is they're giving you one on the brief, even if they nail it, but the reason they give you the second one is because this is a little bit off the brief but this is what I feel. You would probably say, if you were the actor, give me the second one, don't give me the first, correct? That's the dilemma.

Mark Estdale:

It's not a dilemma. It's just make a choice and run with it. Because once you start building an ensemble, we want the brief to be precise. What actors submit expose a brief. Because if actors are submitting wild shit, we've got something wrong with the brief. But with the brief, yes, there are choices to be made. And you could go in different directions. And some actors will give me five variations, all of them wonderful. But again, that takes five times the time.

Randall Ryan:

It does.

Mark Estdale:

To do it, to review it.

Randall Ryan:

Unless you hear one and you're like, I don't care what else they did, that's it?

Mark Estdale:

Yeah. We would never make that decision. So, a self-submission is that's interesting. All you need to do is pique my interest. Because the next stage is getting them in the booth and working with them. And then that is where the discussion opens up. It's just clarity of choice. It doesn't have to be to the brief. It can be, I've got this idea, I think this will be this and give it. Because what you see is choice momentum, life in the performance, it's there. And when something is fully alive and realized and vibrant that you go, that's interesting, I want to go that way. What I'm looking for is talent to work with. As we said earlier, there's 26 productions live right now. It's not just that one role we are casting for. We are casting all the time. And if somebody's showing stuff that's interesting, that interesting gets flagged. It's part of the pool for all the productions. They may not be good for that role, but they'd be great for this one.

Randall Ryan:

Right. And that happens?

Mark Estdale:

Yeah, all the time. People will submit stuff and you go, ah, that's such a great performance, but it's just not right. And it's not just about the performance. You're building an orchestra. It's all about the group of actors. It's the ensemble that is what makes a piece work. And you want different tones and textures, pictures. You want color. It's like an orchestra. If an orchestra was all fucking violins, it'd be dead.

Gillian Brashear:

Right.

Randall Ryan:

Right.

Mark Estdale:

It doesn't matter how virtuoso you are. You're looking for different instruments to give you the thing. So casting is not about the brilliance of your performance for that one thing. It's about that performance in relationship to everything else. But a great performance will always be noted. And it'll go into that resource for the casting team.

Randall Ryan:

So a technical question then on the way that you're doing your thing.

Mark Estdale:

Go on.

Randall Ryan:

Somebody gives a great performance, but it's not what you're looking for on that brief. They are possibly going to be scored something like a two.

Mark Estdale:

But if it's a great performance, it wouldn't get a two.

Randall Ryan:

Okay. So even it's like, they're not going to get this role, you're still essentially saying, by your scoring system, they got a three. Because even though it was a great performance, it's not what you're looking for in that role. Is that not how that would work?

Mark Estdale:

Yeah. But three's good. They can nail it.

Randall Ryan:

I see.

Gillian Brashear:

You bring them in?

Mark Estdale:

I would bring them in and work them.

Gillian Brashear:

How do you deal with people across the ocean?

Mark Estdale:

We don't do any remote recording.

Gillian Brashear:

Interesting.

Mark Estdale:

Because it's all about this.

Gillian Brashear:

Yeah. So people have to come here and record.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah.

Gillian Brashear:

For any of your jobs. Wow.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah.

Gillian Brashear:

Okay.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah. We won't remote ... Well, the thing is if it's one voice in something, then fine. I did one production in lockdown with actors all over the world. We were shipping out the same equipment to everybody. But the most expensive thing about a recording studio is the room you sit in.

Gillian Brashear:

Yeah.

Randall Ryan:

That's right.

Mark Estdale:

And ...

Gillian Brashear:

That's the toughest.

Mark Estdale:

... basically, people in their cupboards, under duvets, whatever, will sound different. And the thing is, you've got a disconnect. The actors are dealing with the technical as well as performance. Some actors are massively technical. Some of the best ones don't know what the internet is.

Randall Ryan:

That is correct.

Mark Estdale:

So the technical side of it, it's always a compromise, it's always a loss, it's always a degradation of what you can do. So we've made that in June last year. That's the way we roll. And we started mid-June, July last year back into full production.

Gillian Brashear:

Do people fly over for you?

Mark Estdale:

For doing stuff from the States?

Gillian Brashear:

Yeah.

Mark Estdale:

There's so many Americans over here now.

Gillian Brashear:

Okay.

Mark Estdale:

Now that was one of the thing is like 50% of our productions are US. And we are looking for studios to work with in the States right now. But we want to be able to plug them into our way of working.

Gillian Brashear:

You might have to go back and rebuild that studio again!

Mark Estdale:

Well, yeah, it still exists. Now, I'm not going to go and do that. We want to do it in a partnership thing.

Gillian Brashear:

So you're looking for a partner over there who can do something with the same type of setup and have the same relationship.

Mark Estdale:

But it's having a really great room to be able to do this. This is fundamentally my playground. And the research element of it I'm doing. You are sitting in the Petri Dish. Everything you do is noted. And so, why does that work, why does ... I've done this for decades. And you notice patterns and you see things and you're going, okay, I'm going to change this and I want to be able to take that further. Now I'm understanding more of the science. The science has caught up with the acting. So the dialogue is now current and live between the cognitive sciences and performance. And it is the most exciting. There's three great books on the subject. The one that really got me is a guy called Dick McCaw. He did a book called Training the Actor's Body. Originally, I thought the most important element in performance is one of the things I watch in casting is the physicality. So, how an actor physically enters a character. You can't do it with a 416 in front of you or a U87.

Randall Ryan:

Well, you can but-

Mark Estdale:

You can but you are caged. You're in a cage.

Gillian Brashear:

Mm-hmm, mm-hmm. You're doing this and working with them.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah, yeah. You can do it wonderfully, animation there. The common practice is to do it in a cage.

Randall Ryan:

Right, right.

Mark Estdale:

But when you release the beast, holy fuck, you get something different.

Randall Ryan:

So another technical question. This mic, small capsule.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah.

Randall Ryan:

How are you getting the depth?

Mark Estdale:

Okay. So, it's a 4060, it's a DPA.

Randall Ryan:

Okay. But what's the technology that makes this give that bottom menu and all that stuff that's around 180 hertz that sometimes you're rolling off, but if it's not there and those harmonics aren't there, you lose that.

Mark Estdale:

You are listening to a voice. For me, performance is a voice in an environment. So, what we want is something that's natural and neutral. That is the focus. Every mic colors.

Randall Ryan:

Absolutely.

Mark Estdale:

And you want a constant coloration. So, there's a distance, the way the mic is placed and everything. We've researched this forever. And it's like working that mic where it is, is like working at U87 at a meter. But you need a good room for it. That's another side of it. And-

Randall Ryan:

So its polar pattern is a little more omni?

Mark Estdale:

Yeah, they're omnis. So, I want a really natural sound to it. And the other thing is the more performance capture you're doing, you've got mics attached to people. Yeah. And they're using these mics on the stage. So the performance capture stage we're building is going to be just a very big sound studio. But it's going to be one that's going to have controllable acoustics because I want to put orchestras in there as well. But it's having that playground because when their new studio comes, to be able to connect all the different rooms in the different environments, that means we could do some really crazy shit. And the crazy shit is something that tickles me.

Randall Ryan:

You realize you can't die because you've got a good 50 years' worth of ideas here.

Mark Estdale:

Oh God, yeah. I know I can't die.

Gillian Brashear:

I got to say ...

Mark Estdale:

But it's ... Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

Gillian Brashear:

Your spirit of experimentation, I applaud. That you're constantly curious and experimenting to get to a more refined connection and truth. I really appreciate that.

Mark Estdale:

I guess so.

Gillian Brashear:

Yeah, yeah.

Mark Estdale:

Yeah, so it's ... Yeah. You only have one life.

Gillian Brashear:

Mm-hmm.

Mark Estdale:

And it's like, if we don't enjoy our craft and what we do and can't be supportive in each other's shit, what the fuck's the point?

Randall Ryan:

I'm kind of with you.

Gillian Brashear:

I agree. I agree with you fully. Randall?

Randall Ryan:

Gillian?

Gillian Brashear:

All right.

Randall Ryan:

Sure.

Gillian Brashear:

Thank you so much, Mark.

Mark Estdale:

Thank you for being here.

Gillian Brashear:

Mark Estdale, it's fantastic.

Mark Estdale:

Thank you. It's lovely to have you in our day in the Petri dish.

Gillian Brashear:

Oh, my gosh.

Randall Ryan:

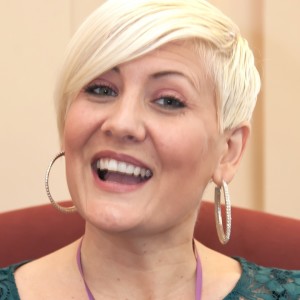

I already feel a little more moldy. My cells are dividing as we speak. I don't know. Maybe someone can pull Mark out of his shell someday, right? I really enjoy hearing his perspective and it's a joy to feel the passion that he's got for creativity and really just for our industry. Let's Talk Voiceover is hosted by Gillian Brashear, actor, director, visionary, and me, Randall Ryan, owner of HamsterBall Studios, delivering the world's best talent virtually anywhere. And I can also be found at thevoicedirector.world. You got comments, questions, or just want to let us know what you think, reach out at info@letstalkvoiceover.com. Find us at all your favorite places, GetPodcast, iTunes, Stitcher, Apple Podcast, Podbean. If there are podcasts, we're probably there. Thanks for listening, and we'll talk again real soon.

Thursday May 27, 2021

Let’s Talk Voiceover - Episode 33 - Misty Lee

Thursday May 27, 2021

Thursday May 27, 2021

Sometimes you're having so much fun that a podcast pops out. That is what happened when we talked with Misty Lee. Misty is an awesome voice actor who is also an awesome magician. Yup. Really. As a lifelong performer, Misty talks honestly about the privilege of being a voice actor. And with a track record of success that includes Ultimate Spider-Man, Grand Theft Auto V, The Last of Us, Star Wars Battlefront, Disney Infinity, and more, Misty helps to remind us all how wonderful and magical this business really is. Invest your time to listen to Episode 33 and you'll walk away with a smile and incredibly valuable advice that's hard to find anywhere.

Tuesday Feb 23, 2021

Let's Talk Voiceover - Episode 32 - Hall Hood

Tuesday Feb 23, 2021

Tuesday Feb 23, 2021

Ever wonder what it would be like to hear from the writer who brings the words for our voices? Hall Hood is a narrative designer who specializes in creating immersive player-driven stories. His credits include games published by Electronic Arts, Sony Entertainment Corporation, and Disney. He has created stories and characters for the Star Wars, Dragon Age, and Mass Effect franchises, and also written for mobile games and console titles like Ghost of Tsushima for Playstation. In addition to his work as a writer, Hall mentors aspiring narrative designers, consults with production partners for Eko.com’s interactive video series, and provides expert support on other projects in development. Plus, he's really funny! Check out the podcast.

Tuesday Jan 12, 2021

Let’s Talk Voiceover - Episode 31 - Mark Oliver

Tuesday Jan 12, 2021

Tuesday Jan 12, 2021

Mark Oliver is a voice acting badass who does what he does in film, animation, and videogames. From Wood Man in the Mega Man animated show to Batroc in the Marvel Video Comics to Miles Dredd in the Max Steel franchise, and roles in Dungeons and Dragons Online and Lord Of The Rings Online, Mark has a fascinating background as a professional musician, actor, and film director. He talks about being authentic, and the advantages you can find by engaging in life to find your motivations. Take a lesson from a voice of experience, and check out this episode with Mark Oliver!

Brian Talbot:

Have I offended you yet?

Mark Oliver:

I don't think of myself as being... I'm not easily offended.

Randall Ryan:

But, well if that's a goal, I mean, we can make that a goal.

Brian Talbot:

(Laughing)

Mark Oliver:

Then throw the gauntlet down before you gentlemen.

Brian Talbot:

The gauntlet has been laid down. Yes, I will meet that goal. I absolutely freaking will. Ask anyone who's listened to more than three of these shows, they'll tell you.

THEME MUSIC

Brian Talbot:

As the grandson of German film pioneer, David Oliver, you might say that Mark Oliver was born into the business. While not exactly true, the apple sure didn't fall far from the family tree. You see, Mark Oliver is a voice actor, known for his portrayal of the sinister Lord Garmadon in Lego's Ninjago. Vancouver-born and UK-raised, Mark has become a common sight around the animation world. From Wood Man in the MegaMan TV series to Batroc the Leaper in the Marvel Superhero Adventures to Monstrux in Nexo Knights, Mark is a signature badass, both on TV and in video games. Some of his narration work includes Smithsonian's Hell Below and National Geographic's Hitler's Last Stand.

When he's not working in the studio as a voice actor, Mark spends his time working as an independent filmmaker, and his experimental short film, Elvis: Strung Out, received first prize at the International Festival of Oberhausen, Germany. And then to bring this all full circle, his latest film project is a feature-length documentary on the career of his grandfather, German silent film producer David Oliver. Lots of creativity going on here. So, Let’s Talk Voiceover, Mark Oliver.

Mark Oliver:

Yes, let’s.

Brian Talbot:

Thanks for being here. Thanks for spending a little time with us. How fun! A lot of our guests and a lot of the people we talk to are voiceover through and through, and while that's a fabulous way to make a living, my gosh, how fun is being an independent filmmaker?

Mark Oliver:

Well, it's all fun, and I see all of these things as being intimately connected. I mean I started as a film historian at school, and I guess that came as a consequence of being interested in my family's filmmaking legacy. So I really see, I really don’t see any division between any of these different areas of endeavor. Of course, I love voice acting. When I came back to Vancouver after living in New York City, someone said, "You love getting wasted at parties and doing all those crazy voices. Why don't you pursue that as living?”

Brian Talbot:

(Laughing)

Mark Oliver:

… and I said, "Well, forget it because it's obviously a closed shop. It's going to be like trying to get signed up by the Freemasons or something.” But…

Brian Talbot:

There you go.

Mark Oliver:

… I asked a few people, and they made a few suggestions. I made a demo just using my own gumption, trying to figure out, well, what would people want? Some versatility, some variety. And I find that voiceover is immensely rewarding. It's like getting paid to go in and do your own primal scream therapy or something. When you're an on-camera person, you never get given the variety of roles that voiceover will present to you. And indeed, there are no laws at all governing how big these characters can be, and they're usually much larger than life, and I find it very gratifying to be able to, um, engage all of my imagination in the rendering of these different characters.

Brian Talbot:

Well, that is what makes it really fun. Because on camera, obviously, your physical attributes are the primary determination of what your character is or what kinds of characters you can be; unless the director's willing to stretch the traditional or the precast notions of what that character looks like. With voiceover, you truly can be anything, and that's the fun part of it all.

Mark Oliver:

Well, it also, it's ironic because we live in the midst of this extreme age which is so visually dominated, but sound is still such a mysterious component and affects people subconsciously in a way that they can't even put their finger on. Or, as I say, sound is like the, the thief that comes through the basement door of the imagination and affects people in an extremely provocative fashion. So I'd like to think of this endeavor of voiceover as being a revenge against this era that is determined 98% of the time by visuals. I mean, my God, if you could divorce the voice of Kim Kardashian from the image of Kim Kardashian, and just think, my God, who could this person be listening to this vocal fry? …

Brian Talbot:

(Laughing)

Mark Oliver:

…like what does that tell me about this, this person? So I think about it a lot, and I have the luxury of being able to disappear into these different mediums. And I like to think that it gives me a fresh perspective when I return to the voiceover studio and attack this, that, or the other role. So you're correct.

Randall Ryan:

So when they told you that you could do voiceover but you could not continue to get wasted to do it, how close was that to a deal breaker?

Brian Talbot:

(Laughing)

Mark Oliver:

You know you have to do these things carefully by stages…

Randall Ryan:

(Laughing)

Brain Talbot:

(Laughing)

Mark Oliver:

…so it took about six months. (Laughing) No, I thought it was fine. I mean I should clarify that I come from a family where language is really deployed by most of the people in it to make a living. I mean my father was a criminal lawyer of renown and became a judge of the Canadian Supreme Court and was really one of these kind of Perry Mason figures who very entertainingly was able to sway juries because of his command of the language. It was always a huge, huge thing, not even what you said so much as the musicality or cadence with which we were able to try and convey this, that, or the other point to win an argument.

Randall Ryan:

Right sure…

Mark Oliver:

So, so I think that was my jumping off point. I wasn't somebody who was a trained actor, was frustrated with an on-camera career and then thought, "Oh, I'll investigate voiceover." It's completely satisfying, without having to think about anything else. So I think I might have had a bit of an advantage, as I say, coming from this background where people could so deftly manipulate the English language to convey a point, win an argument, that sort of thing.

Randall Ryan:

Well, sure, if you grew up around that, I'm not an actor, but I had the same thing with my family where I grew up around all these people who, ultimately when they got older, they were salesman and politicians. My father ended up being a lawyer as well. That side of the family would get together, and they were really big on trading insults and arguments and it was all very happy.

Brian Talbot:

So it was like an adult sitcom-

Randall Ryan:

It was like an adult sitcom.

Brian Talbot:

(Laughing)

Randall Ryan:

(Laughing)

Brian Talbot:

.. who were the Simpsons before The Simpsons.

Randall Ryan:

You had to learn how to speak and protect yourself or else you were just going to get run over.

Brian Talbot:

So what was the plan before that, Mark?

Mark Oliver:

Before all that? I mean I was a, you know, scrappy kid who cut my teeth in the punk rock scene here in Vancouver and was in a number of bands. And…

Brian Talbot:

Well, that explains the drunkenness.

Brian Talbot:

(Laughing)

Mark Oliver:

That partially, partially explains it. And we'd had the good fortune of being selected by The Clash to open up for them on their Combat Rock tour, so we did a couple of shows opening up for The Clash. And you know once you get in front of 8,000 to 10,000 personal audiences, you're not going to go back to anything else. So I took care of everything here, wrapped up business, and you know moved to New York City. I guess I wanted to be eyewitness to what was going on in the world of hip hop in Manhattan. So I got to New York City around the summer of '84, I guess it was, and got into an R&B band based in Philadelphia, of all things, which was really cool because that was its own kind of university going from like the punk rock world of like, "Yeah, man, just wing it," to "No, man, you're going to like stay and you're going to rehearse these harmony vocals…

Brian Talbot:

Sure..

Mark Oliver:

… till four o'clock in the morning or however long it takes to nail this shit.”…

Randall Ryan:

Yep.

Mark Oliver:

So you know I met all sorts of people in the music world in New York City and Philadelphia…

Randall Ryan:

Yeah.

Mark Oliver:

…you know I'd be walking down the street and someone would introduce me to a Delfonic or a Stylistic or something like that. And I loved that. I also loved the way that people were using language. It was so romantic and so expressive. So it's not like I, I had to sort of stay close to whatever influences I picked up from my family. I realized I loved everything about language and the musicality of it. So, I did okay and had some gigs doing backing vocals on people's records and stuff like that. But it was a tricky time to be in New York City through the '80s. It was a pretty hard-scrabble existence. Various things happened that meant I just couldn't live in New York City anymore.

Brian Talbot:

Sure.

Mark Oliver:

I came back to Vancouver around '97, which is when the drunken voices at parties started to really become...

Randall Ryan:

(Laughing)

Brian Talbot:

(Laughing)

Mark Oliver:

…“I have to focus on these drunken voices (laughing) if people are going to take me seriously." And I attended a seminar as part of the Vancouver International Film Festival where people were demonstrating how to do these voices for animation. And there was a sort of a Q&A, and I looked at what people were doing. I thought, "Well, this doesn't seem too exotic. It's not too much of a stretch from being wasted at parties and doing this stuff for free." So I thought, "Well, why not?" I wasn't intimidated by studios…

Brian Talbot:

(Laughing)

Mark Oliver:

… because you know I'd cut tons of demos and tons of records already, and you know was comfortable with going off, just leaving.

Brian Talbot:

Sure.

Mark Oliver:

So it didn't seem like too much of a stretch. When I showed up to my first session, 90% of the people in the room turned around and said, "Well, who the fuck are you?”

Brian Talbot:

(Laughing)

Randall Ryan:

(Laughing)

Mark Oliver:

(Laughing)

…Because I just sort of arrived.

Brian Talbot:

So it was a welcoming crowd. That's very nice.

Mark Oliver:

Yes, such a welcoming embrace. Because I was there doing this principal character, I'm sure everybody in that room would've thrown their hats into the ring to get that role, but here was this total stranger being a king of a planet in outer space. And um I'd like to think that I equated myself with aplomb in that environment, but I also had wonderful people to observe and study from, so I was able to learn a tremendous amount from just the very talented people who were working around me. They're still my colleagues to this day. You know since that time, I realized, oh my God, I have to take this thing seriously. It's not a party trick anymore…

Brian Talbot:

Right…

Mark Oliver:

… This could be a real thing. I looked at my first check and I thought, "There's got to be some mistake in accounting.” They couldn’t possibly…

Brian Talbot:

(Laughing)

Randall Ryan:

(Laughing)

Mark Oliver:

….they couldn't possibly pay this amount of money for what we did. We were just goofing around.

Brian Talbot:

For what I did? Are you kidding me?

Mark Oliver:

We were just goofing around. And people assured me like "No, that's pretty much par for the course." And since then I had to really kind of conduct forensic research into the kind of voices that we use on a regular basis and certainly many other voices that, if they didn't already have a presence in animation, could quite possibly sometime in the near future. This was really before people had fast internet so that meant like…

Brian Talbot:

Sure

Mark Oliver:

… going to the libraries and studying regional voices and dialects and accents. And I realized I was just already interested in that…

Brian Talbot:

Yeah

Mark Oliver:

… I loved it. I realized I'd found my métier. So you brought up a really good point about when people ask you like, “Yeah, you know think about playing that game, that voiceover game.”

Brian Talbot:

How do you get into it? You become a student of it. That's the best advice I can give them is become a student of voiceover. So if you're going to play golf, then become a student of golf, understand everything about it. You want to be an actor, go become a student of acting. Figure out everything about it. You know all the same actors are in the Scorsese films. All the same cast members go from one Coppola film to the next Coppola film. So all these guys get their troops of people, it's like small theater troops, and they work with them because they know how to work together, and that becomes incredibly, incredibly valuable. That was something that I started doing when I started acting, and especially doing indie films and stuff like that. I found three or four core groups of people of writer/director/videographer teams that I could work with from project to project to project. That was just simply a result of becoming a student of what it is that you're trying to accomplish. And that's exactly what you were doing at that point in time.

Mark Oliver:

Yeah. I wasn't rolling my eyes contemplating all of the homework. I just kept returning back to the thought, "Oh my God, the English language is fascinating.”

Brian Talbot:

Isn't it though?

Mark Oliver:

It fascinates me. It fascinates me. I’ve been, I was very lucky, when I was in New York City, I had any amount of friends from the South who'd say, "Well, you should come down, come down to Tennessee for a week." And I would go down to Sewanee or be around Chattanooga and just to collar people on the street in a town or whatever. You'd be like, "Do you mind repeating what you just said?”…

Brian Talbot:

(Laughing)

Mark Oliver:

… Not because I couldn't understand it the first time around, but it was just so beautifully delivered in such a lazy cadence. I just thought, "Wow, the United States is amazing. It's just a universe of voices." I'd think to myself, this is long before I got involved in voiceover, and I thought, "I'm going to file that away for future reference." I don't know why. And lo and behold, the opportunities arise where you can deploy that knowledge. When people ask me what to study, it's never been easier because you have YouTube, you have Vimeo.

Brian Talbot:

Sure.

Mark Oliver:

…and I never really, I don't really like to watch movies. I mean, I will, for references and stuff like that. But I find it to be a bit of a cheat. And if you wanted to craft something unique or something that belonged to you, then I'd rather be on the streets of Austin or whatever talking to people and not listen to Tommy Lee Jones.

Brian Talbot:

Matthew McConaughey trying to do it. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Mark Oliver:

Yeah, yeah, that sort of thing. Side note, my dad, during the war, he worked for British Intelligence where he worked in a branch of MI5. And he spoke five languages fluently.

Randall Ryan:

Oh, my.

Mark Oliver:

He would be charged with the responsibility of apprehending SS or Gestapo men who are on the run with assumed Wehrmacht identities and have to spirit them through the different sectors of Berlin, French-held Berlin, Russian-held Berlin, etc., etc., to get them back to British-controlled Berlin. So that meant that he would have to slip in and out of different voices and accents and languages to do that. And so I was very lucky to have somebody like my father. He regarded all of this pursuit as, how believable do you want to be? You are being parachuted 10 miles behind enemy lines, and you must be able to pass unnoticed by the local populace…

Randall Ryan:

Yeah.

Mark Oliver:

…So I take all that sort of stuff very, very seriously. So I don't know whether people, when they listen to cartoons, for example, consider that I and many of my other colleagues approach all of this kind of forensic research with tremendous seriousness just to be able to give you a really compelling talking tomato, for example.

Randall Ryan:

Right.

Mark Oliver:

(Laughing)

Brian Talbot:

Well, I think that's a really important point. The other thing that people do is, "I do a bunch of funny voices. I want to get in voiceover. I can do George Bush, 'Not going to do it.'" Well, no, that's Dana Carvey's impersonation of George Bush…

Brian Oliver:

Yeah.

Brian Talbot:

…So you're not doing George Bush. You're doing Dana Carvey doing George Bush. Now, if you had your original spin on it, and it was really, really good...

Randall Ryan:

Right

Brian Talbot:

..and oh, by the way, most people don't need impressions of other people. They need their own original characters. You know I was listening to someone not too long ago, and they're like, "Oh, I've got this voice, and it's this alien character, and so I'm going to do Marvin the Martian." No, no. That's someone else's character. That's not your original take on what it is.

Randall Ryan:

Right

Brian Talbot:

That becomes so important in being able to not only book work, but be authentic and be convincing and really make that character yours.

Randall Ryan:

Well, and that's one of the things that concerns me about some of the things that I see with internet casting and with people thinking that they can do this on their own is that type of lack of creative thinking. I have this stereotype in my head, and so that's what I'm looking for, and that's how I'm going to direct, or that's what I'm going to ask the actor to do without allowing that actor... Especially, I'll say this about Mark, you have done some of the best villains for me, period. Because they're not just villains. They're complex and textured.

Brian Talbot:

Not just badass, but scary badass.

Randall Ryan:

Exactly,…

Brian Talbot:

Yeah yeah

Randall Ryan

…just that psychological. Even if the script isn't really totally written that way, just that ability to dig in and get that. That's coming from you. That's not coming from me. It's not even coming from the writer necessarily. It's coming from allowing you to bring that piece to yourself. That's one of the things that really worries me with some of the trends that I'm seeing once you take out those people that understand what acting is. And I'm saying more on this side of the glass than on your side of the glass.

Mark Oliver:

Well, first of all, thank you for the kind and completely misplaced compliment.

Randall Ryan:

Yeah, right.

Brian Talbot:

(Laughing)

Mark Oliver:

No, no. Well, now I know what kind of estimation I have to live up to next time, so the stakes are raised. Thank you.

Brian Talbot:

You just raised the bar. I hate that.

Mark Oliver:

You raise the bar. But it's true what you say. Because I talk to students and they feel safer choosing to be a facsimile of George Clooney or a facsimile of this person and the other person because they confuse that with a degree of professionalism and that these people, because they are famous actors, have a kind of a currency and value. Therefore, I, by extension, must as closely as possible approximate their voices. I say, no, because then you're never going to stand out of the crowd. As an actor, I really don't like being confronted with sort of sound alike projects.

Brian Talbot:

Oh, I hate those.

Randall Ryan:

Right.

Brian Talbot:

Yeah, those are the most annoying things. My favorite answer, and I've yet to use it, but one of these days I will: "Yeah, we're looking for a Sam Elliott." "Well, you know you can call up Sam's agent and he'll put you in touch, and you can book Sam. If you're really looking for Sam Elliott, then he's available. He's alive. He's still working. You know go get Sam Elliott.”

Mark Oliver:

(Laughing)

Mark Oliver:

Well, it could be laziness on the part of the casting person or the producer. I really don't know. Or…

Brian Talbot:

Yeah

Mark Oliver:

…that people just don't have adjectives at their fingertips to properly describe the characteristics that they're looking for.

Randall Ryan:

I think you've hit the nail on the head with that. They don't. I've sat in on other people's sessions, or I've been hired to do it, but they really don't want me to direct. So I'm listening to some of these people who don't do this, and I'm listening to these people that don't have reps, and they also don't have the imagination to do it. They don't know how to tell somebody what they're looking for, and it is exactly that. They don't have the adjectives. They don't have the stories. They can't get down to the musicality and to the kernel of what it is they're looking for. All they can do is shortcut it to “Um, yeah we're looking for something that sounds like Morgan Freeman. We're looking for something that sounds like..." fill in the blank because that's all that they can imagine. That's where you get the stereotypical read. "Well, we're looking for a villain, so [inaudible 00:20:27]. Like, "Ah, no.”

Brian Talbot:

(Laughing) I like that villain. That was an awesome villain. That was just-

Mark Oliver:

I worked on a religious-themed project.

Brian Talbot

(Laughing)

Mark Oliver:

Within this, within the stories, there's the character of Satan that they were trying to cast. I thought, "Well, this'll be fun. I can really sink my teeth into this…

Randall Ryan:

Umm hmm

Mark Oliver:

…challenge”, so I showed up for the casting, and I felt I was prepared. They said, "Mark, whenever you're ready, go." And so I started, and I didn't get past the second sentence before the casting person stopped me and said, “Um what's your name?" "Mark. Mark Oliver." "Mark?" "Yeah." "I don't know whether you got the memo, but um Satan in this story is the bad guy.” And…

Brian Talbot:

(Laughing)

Mark Oliver:

he said it like a bad guy, "But the way it's coming out, the way you're doing him is, well, frankly, he's kind of sexy. Did we tell you that he was the bad guy?" I said, "Interesting observation. Well, I'm just going with the whole thought that Satan is a very seductive, attractive character.

Brian Talbot:

Thank you.

Mark Oliver:

Because he is so attractive, he will bend people to his will and get people to do a lot of things that they normally would feel very uncomfortable doing. Do you see where I'm going?" They're like, "Yeah. Did we say that he was the bad guy?”

Randall Ryan:

(Laughing)

Brian Talbot:

(Laughing)

Mark Oliver:

I know and at the end of the day, they went with, [inaudible 00:22:00].

Brian Talbot:

Right, of course.

Randall Ryan:

Oh, man.

Mark Oliver: